Bruce Benderson

Love Is Not for Sale

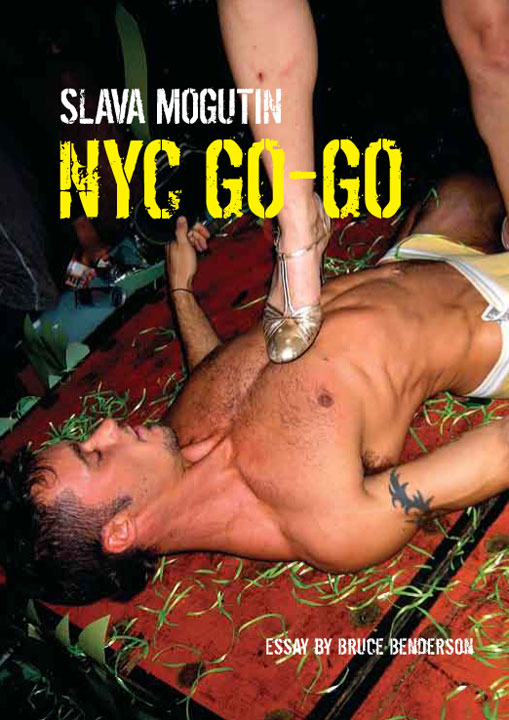

Essay for Slava Mogutin's monograph NYC Go-Go

NYC Go-Go, powerHouse Books, Brooklyn, 2008

NYC Go-Go, powerHouse Books, Brooklyn, 2008

Things haven’t changed, and no one knows it better than Slava Mogutin. Born in 1974 in Siberia’s industrial city, Kemerovo, he came to the United States in the mid-nineties during a time of greed in his own country, when cutthroat attempts to wrest control of Siberia’s resources were becoming known as the Aluminum Wars. Mogutin was the very first Russian to be granted US asylum on the grounds of homophobic persecution, with the support of Amnesty International and PEN American. His radical queer writings and performances—including a very publicized “marriage” to an American man—had made him persona non grata in newly capitalistic Russia.

Too bad that his 1995 touchdown in New York coincided with a low point in American urban libido: Mayor Giuliani’s “quality of life” campaign against the porn shops, backroom bars, go-go dancers and peepshows of a soon-to-be-sanitized Manhattan was in full swing. And another, more covert war was going on: the underclass on the streets of the city were being forced into the outer boroughs to lead lives not so different from the poor of Russia’s suburbs. Greed was winning out in America, too. Did Mogutin really think he would find another reality after traveling all those kilometers? Seeing life in the United States merely finished an equation. Any illusions about the personal freedoms of either economic system he may have had were kaput.

If Mogutin was able to maintain any belief in freedom, it was and still is located in the inviolable autonomy of the male body. And this, not so incidentally, started with his own. It is no surprise, then, that he appeared on a 2002 cover of Index magazine buck naked, which became his entrée into the New York art scene, through Manhattan’s carnivalesque downtown circles. At the time, he owned little more than his physical assets and several excellent books in Russian he had written and been known for in the old country. Nevertheless, Mogutin had no intention of living in a Little Russia in this new land. His switch in emphasis from writing to the creation of images came from a need to escape a confining linguistic reality, and in doing so, he accomplished a marvelous ambition. With partner Brian Kenny and their ongoing multimedia project SUPERM, he became internationally notorious in galleries throughout the Western world. This was his way of achieving a dynamic, yet fluid, identity. No single country may claim him.

It would be easy to interpret Mogutin’s reliance upon the image purely in terms of his need to transcend the limits of language, to become international, but his assertion of visceral, often sexual imagery speaks of something much more complicated, much more subversive. It is partly related to the relationship enjoyed by many gay men to the body and the implications that stem from this physical obsession. There is, I think, in the majority of men, gay or not, a tendency to develop a large segment of their identity around physical desire. In the heterosexual world, this overweening drive for conquest is often curtailed and channeled into tenderness, as well as the creation of a family, by the humanist mentality and social aspirations of the women with whom they’re involved. But when the laser beam of desire emanating from two men is directed entre eux, there are virtually no limits to its outpouring.

Hail to thee, bottomless fount of promiscuity. Mogutin is typically male, and the energies that interest him are sexual. To our good fortune, from this cauldron of desire flow all kinds of concoctions: ironic insights about what we think makes a man a man; jokes about the implications of straight male bonding; brash pleasure in the international brotherhood of perverse eroticism; the sexual undertones of the military and athletics; objects found on the floor when sex is in the air. For as any gay man knows, sex can put you in the strangest situations, bending the wires of the social structure, high-jumping language barriers, demolishing the boundaries of class, turning every night topsy-turvy with pleasure. It can pair the banker with the street boy; or it can make a Russian cadet fucking himself with a cucumber look like the peer of a German skinhead indulging in “water sports” or a New York bar patron mouth-tipping a go-go dancer’s penis.

To completely grasp Mogutin’s approach to sexuality we must understand how it interfaces with his profound disillusionment with the two major economic systems, from the West and the East. The exploitation of Russia’s vast resources by corrupt billionaire oligarchs is, to some degree, the mirror of the swallowing of America by corporations; Mogutin’s banishment from the country of his birth because of a homosexual identity goes hand and hand with the sanitization of Manhattan for the enjoyment of one puritanical class only; Russia’s problems with Chechnya are an echo of our war against Islam and our cultural naïveté and xenophobia. Wherever Mogutin has gone, he has witnessed the degradation of supposedly idealistic political systems, the exclusion of certain segments of the population. The American art world is no exception: its call for self-promotion, its slavish kowtowing to trends, its blatant deal-making or networking strategies often serve to put real talent last on the list. Mogutin has, then, witnessed the disenchantment of the humanist ethos almost everywhere, in politics and in culture; and he has the biography, the hurt, the history of struggle and the ambition to portray it much more clearly than most of us do.

In his eyes, the souls of human beings have been stripped as naked as the boys in his photos, but he will have his desire because it is inextinguishable. He has learned the hard way that what is left when the Cold War is over is nothing but the abandoned but still libidinal body, and he has tried to point this out in a celebrative way. What he perhaps didn’t expect, but now knows with increasing sophistication, is that although the body cannot be eradicated by all these disillusioning forces, although it is the only thing that remains intact and belongs to us, it still and increasingly does become a heart-breaking—or joyously perverse—mirror of the same exploitations. NYC Go-Go is exactly that: an expression of the indomitable glory of desire, even as it learns to identify itself with exploitation.

In my excursions into the night of downtown Manhattan with Mogutin, I noticed a weird phenomenon. So similar were the scenes we visited to those I used to frequent in old Times Square that even a few players I had known there ten years hence had resurfaced. Their old values were intact, and their only thought in the go-go dancing, lap dancing or cruising they did, and which Mogutin photographed, was the hope of making a buck. What astonished me, on the other hand, were the others. Like the former hustlers of Old Times Square, they were dancing half-naked on the bar, their cocks lolling within their nearly transparent underpants or occasionally peeking out of it, or jutting forth in a codpiece fashioned from a sock and kept erect with rubber bands that served as a cock ring; their underpants slipping far past the butt crack; their dancing lascivious; their bodies mocking the new anti-sex laws. But they were doing it, they told me, purely for something they called fun. These were young men from the middle class, who didn’t need the money, and I was greatly perplexed by them, until the behavior of everyone—middle class and underclass, both of whom appear in this volume—came together in one epiphany, the realization that a very common metaphor for desire itself these days is prostitution.

This metaphor embraces so much about our current civilization. In the sleazy gestures of go-go dancers, the naked gyrations of partiers at hole-in-the-wall clubs and the chance exhibitionists, we find desiring bodies in deliberate but often sham postures of exploitation, aping prostitution as a way of cruising or partying. And most incredible is the fact that many aren’t forced to. Postures of exploitation are, instead, their joy, their choice, their wielding of power and even their quest for love. The language of prostitution may be, then, the only means of erotic communication available to some in our new society of exploitation. And what better artist to serve up this disturbing metaphor than a person who has seen himself stripped of nationality and set loose in New York as an artist on the make at the moment when all differences between East and West were being ground down into twin models of cynical capitalization?

Slava Mogutin has understood that exploitation is the new flirtation. The pleasure is in the showing. So, go ahead. Look.

© Bruce Benderson, 2008